- Isabel Hicks Chronicle Staff Writer

- May 6, 2023

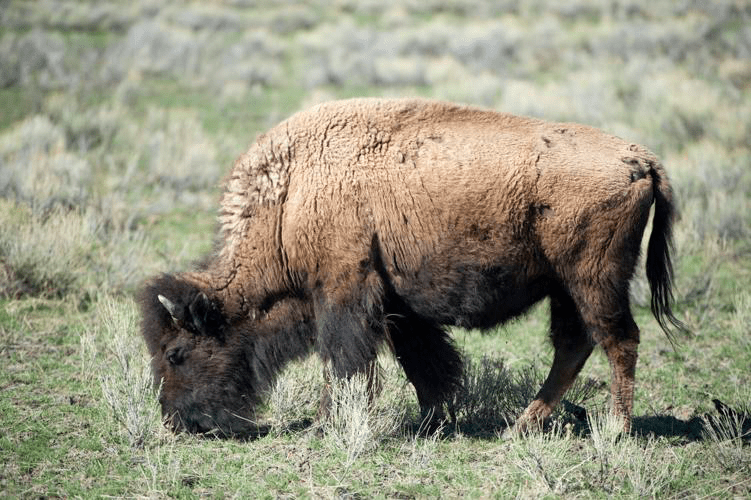

Calls to change how Yellowstone bison are managed have been given new life this spring, following the deadliest year on record for the national park’s wild herds.

Nearly 1,200 bison were killed by tribal and state hunters this year, after a harsh winter drove the animals to leave the park in high numbers. That’s close to one-third of the park’s bison population, which hovered around 6,000 at last count.

Aerial footage from wildlife groups show the bison cull near Gardiner, where blood and scattered carcasses, picked over by birds, litter Beattie Gulch.

The animals leave in search of better food and calving grounds. But once the bison cross outside their defined range, they can be shot by tribal and state hunters.

The hunt is the result of decades of debate on how to best manage bison in the Yellowstone ecosystem. Because of their genetics, the Yellowstone herds are important to Native tribes — but also deemed a threat by the state’s livestock industry from their potential to spread disease.

It doesn’t have to be this way, environmental groups and tribes say. The deadly winter has again fueled calls for alternatives — like expanding allotted habitat for bison and returning the animals back to Native people. But there are still steep political barriers to any changes.

In exploring solutions, the goal is to get as many Yellowstone bison as possible out of the park alive, said Scott Christensen, executive director of the Greater Yellowstone Coalition.

Managers must cull a certain number of bison annually, so the ecosystem doesn’t get overrun with animals. The Yellowstone bison population has recovered from under 500 animals in 1965 to around 6,000 today.

The cull number is decided by officials involved in the Interagency Bison Management Plan. Created in 2000, the group brings together eight stakeholders, including the National Park Service, Montana Fish Wildlife and Parks, Montana Department of Livestock, and the Intertribal Buffalo Council, to collaborate on managing bison.

But last November, the agencies couldn’t agree on a target population for the bison herds — so no specific cull number was set.

That non-decision meant there was no guidance for how many animals hunters could take. As of April 17, the park reported a record year, removing 1,548 bison from the park population. There were 1,172 animals killed by hunters, 94 consigned to slaughter, and 282 enrolled in a transfer program to tribes.

The cull numbers are always higher in years with harsh winters. In other years, few bison leave the park — in 2021, no animals were removed, and in 2022, only 50 were.

Even still, this year’s numbers are record-breaking. The last winter with comparable numbers was 2007-2008, where roughly 1,350 bison were culled. That year, hunters killed only 166, and 1,087 were sent to slaughter.

Now, hunting is the primary method to manage the population. But there are concerns about the hunt’s severity and safety that could be addressed if the area where bison could roam was bigger, Christensen said.

Hunting occurs when the bison migrate onto tolerance zones around the park — north of Gardiner 11 miles to Yankee Jim Canyon, and west of West Yellowstone onto Horse Butte and the Taylor Fork drainage. Those zones were established to support hunting and limit the hazing of animals back into park boundaries.

But outside of those tolerance zones, wild bison aren’t allowed in Montana, including on public land. That’s because they risk spreading brucellosis, a disease also spread by elk that can cause cattle to abort or produce weak young.

Existing tolerance zones could be improved to accommodate more animals, Christensen said. That means building wildlife crossings and using prescribed burns to recover more native grasses for feed. The Taylor Fork tolerance zone is rarely used by bison, because it’s near impossible for them to access it.

Federal government studies have also found Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge in central Montana a prime place for wild bison restoration, as there’s no cattle grazing in close proximity.

But efforts to move more bison onto public lands in Montana have been stonewalled, both through lawsuits and legislation to prevent any bison restoration in the state.

This month, the Montana Legislature passed a joint resolution opposing wild bison grazing on the CMR refuge, even though the land is federally owned.

Livestock industry interests have resisted compromising about bison restoration in any capacity, and that resistance is stalling progress on the issue, Christensen said.

“Until we can get to the heart of the issue and start to come up with some workable solutions — which I believe there are many — we’re going to be stuck in this cycle of consternation and conflict,” Christensen said.

Yellowstone National Park declined multiple interview requests for this story, saying park staff were busy and there was nothing new to comment on.

Other groups are working to expand bison range outside Yellowstone through returning disease-free animals to tribes.

Jason Baldes, vice president of the Intertribal Buffalo Council and member of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe on the Wind River Reservation, has helped restore bison to 65 tribes across 20 states.

The Yellowstone bison are specifically important to tribes because of their genetics, Baldes said. The Yellowstone herds are ancestors of the last buffalo that remained after they were nearly exterminated by colonizers in the 1800s.

“It’s very important that we get this buffalo back into our diet. It’s important that we restore them to our landscapes. It’s important that people understand the history of what happened to the buffalo and similarly happened to Native people.”

Some of the bison in the Eastern Shoshone herd came from the Fort Peck Indian Reservation as part of Yellowstone’s transfer program.

Robert Magnan, director of Fish and Game for the combined Sioux and Assiniboine Tribes, who also oversees the bison transfer program, said since its launch in 2019, the program has distributed some 300 Yellowstone bison to 28 different tribes across 14 states.

In its first year, the program started with just five animals. But this year, that number expanded to over 100, and it’s expected to be even higher next year.

The program can transfer disease-free animals to tribes after a nearly two-year quarantine process, which tests the bison for brucellosis every few months.

“The importance is it gets the buffalo out of the park alive instead of just killing them,” Magnan said of the program. “But I feel sad for the bison. It’s been years we’ve been doing these quarantines and we’ve never, ever had a positive case.”

Magnan noted the thousand-plus animals that were killed this year coming out of the park — animals he said are worth keeping alive, despite politics.

“What makes me so mad is they don’t test to see if they have brucellosis or not. They just round them up and slaughter them. There could have been some good animals that we could have taken care of,” Magnan said.

That’s what drove the Eastern Shoshone tribe from participating in the bison kill, despite their treaty rights to do so, Baldes said.

Eight tribes have exercised their treaty rights to hunt the Yellowstone bison outside the park, but the competition and limited space for hunting makes the practice dangerous, Baldes said. One member of the Nez Perce tribe was accidentally shot by fellow hunters this fall.

Baldes described it as a slaughter rather than a hunt because Yellowstone bison have adapted to not fear people. That means they won’t run when approached by a human with a high-powered rifle. They cross the invisible park boundary and are gunned down.

“It’s good for these tribes to be exercising their sovereignty and their treaty rights,” Baldes said. “But we have to recognize that Montana opened up the hunt to the tribes to use them as a scapegoat to do their own dirty work.”

While state leaders have hailed the bison cull as an important part of native cultures, “they don’t really appreciate or respect sovereignty or self-determination in any other instance, except for this one, when the tribes can be used as their pawn to slaughter these animals on their behalf,” Baldes said.

But other native hunters, like Tom McDonald, chairman of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on the Flathead Reservation, say the hunt is important for both treaty rights and population management.

Anytime native people can engage in bison hunting like their forefathers did, considering the cultural and spiritual significance, it’s a good day, McDonald said.

“Of the tools you can use to reduce the buffalo to the carrying capacity — as defined by all the contemporary issues today — hunting is always the primary way to manage any wildlife population,” McDonald said. “To return our people to that landscape in such a meaningful way, it’s a win-win.”

The Department of Livestock said the carrying capacity of Yellowstone’s habitat is an important factor for bison management, given how fast the animals can reproduce. Decisions aren’t only driven by the threat of brucellosis, said Montana state veterinarian Marty Zaluski.

Removal of bison from the ecosystem has to happen, regardless of whether they have brucellosis, Zaluski said. But because some 60% of Yellowstone bison have been exposed to the bacteria that causes the disease, their options for relocating are highly limited or shut off.

Because of its wildlife, Montana is one of three U.S. states to have additional safeguards to prevent brucellosis from infecting cattle, Zaluski said.

The state has a designated surveillance area around Yellowstone, where cattle are at elevated risk for brucellosis because of overlapping range with bison and elk.

Managing the DSA involves testing 90,000 cattle annually and costs the state about $2 million a year, Zaluski said. But it’s the lynchpin for Montana’s brucellosis-free status, which allows ranchers here to export cattle with fewer testing requirements.

Montana lost that status once in 2008, when brucellosis was found in two herds two years in a row. That meant ranchers were subject to 19 different testing requirements and lost market opportunities from other states — ultimately costing the Montana cattle industry between $5 and $15 million, Zaluski said.

Still, officials found it was likely elk that spread brucellosis to those cattle, rather than bison. There hasn’t been a recorded case of bison to cattle transmission for brucellosis.

Just because there hasn’t been a case doesn’t mean the risk isn’t there, Zaluski said — more bison have been exposed to the disease than elk have.

“When you compound that higher level of disease prevalence with the fact that bison use geography and winter range in a way that’s much more similar to cattle than elk do, that makes it really difficult to say that bison and cattle can be out on the range together,” Zaluski said.

The state has already done what it can to restore bison, and the range around the park for them has slowly expanded, Zaluski said. Moving wild bison elsewhere in the state would probably require another costly surveillance area, he added.

“The challenge with bison management is that the easy answers, the low hanging fruit, have been picked already,” Zaluski said. “We have already allowed bison to an area that is manageable and mitigated the risk to cattle.”

“Going forward, I don’t see an easy way for us to continue that range expansion,” Zaluski said.

Still, some groups have called upon the federal government to intervene. The Gallatin Wildlife Association sent a letter to U.S. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, Montana Democratic Sen. Jon Tester, and leaders in the Forest Service and U.S. Department of Agriculture, asking them to do something about the management situation.

“The bloodshed from killing defenseless bison flows deeper and redder than ever… we are allowing these herds to be decimated, suffering, and injured, while at the same time, many officials seem to behave in willful ignorance to the severity of the problem,” Gallatin Wildlife Association President Clint Nagel said in the letter.

“We firmly believe you could help develop a better, more scientific approach in bison management should you choose to do so,” Nagel wrote.

The federal government has the authority to move bison to federal lands, like the CMR wildlife refuge, Nagel said. As of Wednesday, no one had responded to his letter.

The Alliance for the Wild Rockies sent a similar letter, asking for the federal government to use its authority to expand bison range.

The group has also helped sponsor eight billboards throughout the state, reading, “It’s not a hunt. It’s a slaughter,” to raise public awareness about bison management at Beattie Gulch.

Both wildlife groups are also petitioning for the Yellowstone bison to be listed as endangered. The species is up for consideration for listing, after the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service opened a year-long study to explore the option last June.

That would shut off hunting opportunities for the buffalo until its population recovers enough to warrant delisting, said Mike Garrity, director of the Alliance for the Wild Rockies. It would also force managers to agree on the animal’s carrying capacity in the Yellowstone ecosystem.

“Having the state of Montana decide how to solve this problem — it’s like asking Mississippi to solve the civil rights problem in the 60s. They were part of the problem,” said Mike Garrity, the alliance’s director.

“The federal government stepped in then, and the federal government needs to step in now to (protect bison).”

Isabel Hicks is a Report for America corps member. She can be reached at 406-582-2651 or ihicks@dailychronicle.com.