Writings

To Be A Chief

TO BE A CHIEF IS TO SERVE

Recently I had the privilege of being invited to participate in the Cheyenne tribe Fort Robinson Outbreak 400-mile Spiritual Run, from Nebraska back to the reservation in Montana. I had done this once before some years ago and I knew how challenging it was on so many levels: the wind and freezing cold, endless roads rising and falling through the Black Hills and prairies, starting before daybreak, and often ending late at night. Back then I ran many legs of the Run. This time, my offer to help in any way resulted in driving the supply van and sorting out the vast quantities of food, water, and supplies needed by the 80-100 runners along the way.

The first morning we gathered in Lame Deer, near the memorial for Chief Dull Knife, Morning Star, prior to driving to sacred Bear Butte for a prayer service, then on to our run starting point at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. Chief Phillip Whiteman Jr, and his wife Lynette Two Bulls, were busy organizing the runners. I noticed a solitary figure standing beside a truck with a porta-potty mounted on a trailer. The man was tall and calm, very reserved, I assumed he was a father or grandfather to one of the runners. And I will admit that in the moment I thought: “At least I’m driving a van full of fresh smelling supplies, not pulling a toilet.”

The drive to Fort Robinson took many hours. We arrived late that night and spent more hours organizing the sleeping arrangements and preparing food. When all was ready, Phillip took out a drum and the solitary man came forward to join him in a spiritual chant and prayer. At the conclusion, Phillip introduced the man – Chief Alan Little Coyote, the Chief of both the Northern and Southern Cheyenne tribes, one of the largest tribes in North America. Chief Alan looked out at the runners and said: “You may have seen me today, following along behind at the end of all the trucks and vans. When Chief Phillip asked me if I could help with the Outbreak Spiritual Run, I told him that I would come only if I could perform the most needed service. He asked if I would pull the porta potty. And of course, I accepted immediately. To be a Chief is to eat last, to make sure everyone is safe, especially the children and elders, before going to bed. I honor the sacrifices you make participating in this Spiritual Run, which will test you and not be easy. But I am your Chief, and it is my sacred duty to serve.”

I went to bed that night reflecting on his words, and trying to recall any American leader – mayor, Congressman, President – who I had seen to serve with that degree of humility and respect. And of course, Chief Alan Little Coyote stands alone.

Yellowstone Passage

A short story by John S Newman

There came a moment when the water flowed west.

“Is this it?”

“Can’t be. Cap’n?”

A rustling of weaponry, maps, paraphernalia. Captain Clark snapped his fingers and York brought the scope. Clark looked this way and that.

“By god, I do believe so.”

Merriweather’s loyal dog, Seaman, whined; the baby, Jean Baptiste, cried, shushed by Sacajawea; her man Charbonneau signed himself with the cross.

Lewis came forward. “So, it’s true, there’s no through passage.”

“From the States to the ocean?”

“Wasn’t that our mission?”

Clark wearily removed his hat, rubbed his thinning reddish Scots hair, handed the scope back to his slave. “We passed that by back on the Missouri headwaters, at Three Forks, if you recall. Seemed fairly obvious.”

“Well, I just hoped…”

“Hope is out there, partner.” He raised a hand towards the horizon as Private Colter fell to his knees, making a rough prayer that after the grinding upstream pull the Great Divide was crested and their Voyage of Discovery could start anew. “Next stop, the mighty Pacific!”

We stand at that spot, my son about to be married, a daughter off to college.

“How could they even know it was all downstream from here?” Henry asks.

“It’s like, nothing but trees and mountains.” Monica observes.

“They had pretty good guides,” I say. “Sacajawea was from a nearby tribe and Toussaint was a trapper.”

“So you have telescopic eyes and can tell there’s an ocean out there?”

We share a laugh as I step away from them, but with eyes in the back of my head. They’re so young, hopeful, eagerly optimistic. How can a father not cherish a belief that he can see into their futures? But deep down knowing we were all three collectively in perfect ignorance.

“For the tribes, this was their home. They had no idea what was coming. And for everyone that came after, they had no clue what was here.”

I knew from their Journals about a long, wet Oregon winter just above high tide, followed by an urgent trip home, where modest fame awaited some, a death defying run for Colter, uncertain freedom for York, obscurity for Sacajawea, and suicide for Lewis, with Seaman pining away to death atop his grave. I imagined that Clark knew more than most that it was the end of the frontier, a land of no restraints with few fresh tracks on unplowed earth.

“I just wanted you to see this for yourself.”

“What, a whole lot of nothing?”

The elevation and cool clear air infuse a soaring sense of raptor levitation to the moment.

“No, the possibilities.”

The house is silent, the only sound my wife’s breathing, and the curious grousing of the dog, chasing feathered dreams.

I consider getting up but soon doze off, and feel the bed drifting, as if on a broad river, through canyons where snow hangs on the ridge tops in July, and the sun is always setting. The flood stage has passed. The cut banks are low to the water. I run my fingers through the tops of tall grasses. Lupine is in bloom, the scent dizzying on the breeze.

The river carries me to a place where acrid steam rises from the meadow, a sulfuric mist in the air. Over there, a bull elk picks up the scent of wolves emerging from all sides. Eyelids fluttering, I tremble as the lone prey stares about, seeking protection with the herd, which is nowhere to be seen.

I try to wake up, breathing erratically, struggling to know if the ensuing carnage is real or imagined, unless the potency of dreams increases over time, until that is all there is.

My wife nudges me. “Can you roll over? You’re sounding awfully apnea-tic.”

I rise and sleepwalk away from her in the dark. Hoar frost soil crunches beneath my feet, a low wind filters through the pines. The startling sound of a midnight helicopter brings me back, and I find myself facing a cold fireplace, and a mantle bearing images from some faraway place: a trio of vaguely familiar faces, one young man, two cherubic siblings, squinting beside a blizzard-weathered sign: Lolo Pass.

The return to bed leads along darkened hallways, passing empty rooms filled with long-forgotten memories: high school trophies, wedding photos, college diplomas.

“Where have you been?” she asks, drifting softly in braided channels.

I lay down in shallowing currents that disappear in alluvial graves, the sound of my whispered voice barely audible above the roar of distant rapids in a high country I will no longer explore.

“Yellowstone.”

Warrior Trail

Warrior Trail

My home sings to me

there on the Powder River

the land of my ancestors

who wait in their graves

beckoning me to press on.

The song burns in my blood

warmth on a frozen night.

The moon shows the way

along the White River

silver in the hard freeze.

A thousand porcupine quills

pierce my face and fingers

the wind relentless as death.

I rip open my robe and shirt

my heart embraces the cold

beating in fiery harmony

with pain paved down this road.

To be a warrior is to know pain

given and received, the battle

won in the unequal balance.

I venerate my suffering

the exquisite mutiliations

of Custer and Fetterman, though

in death they wounded me more

imprisoning our few survivors

then shipping us like sheep

to die on foreign soil.

But there comes a time

when a warrior breaks free

the song clear in his heart.

Tipi Ring Ranch, local history, Shawmut, MT

Archived at the Montana Historical Society

BEFORE AND AFTER THE BUFFALO YEARS

A history by John S. Newman

May, 2022

INTRODUCTION

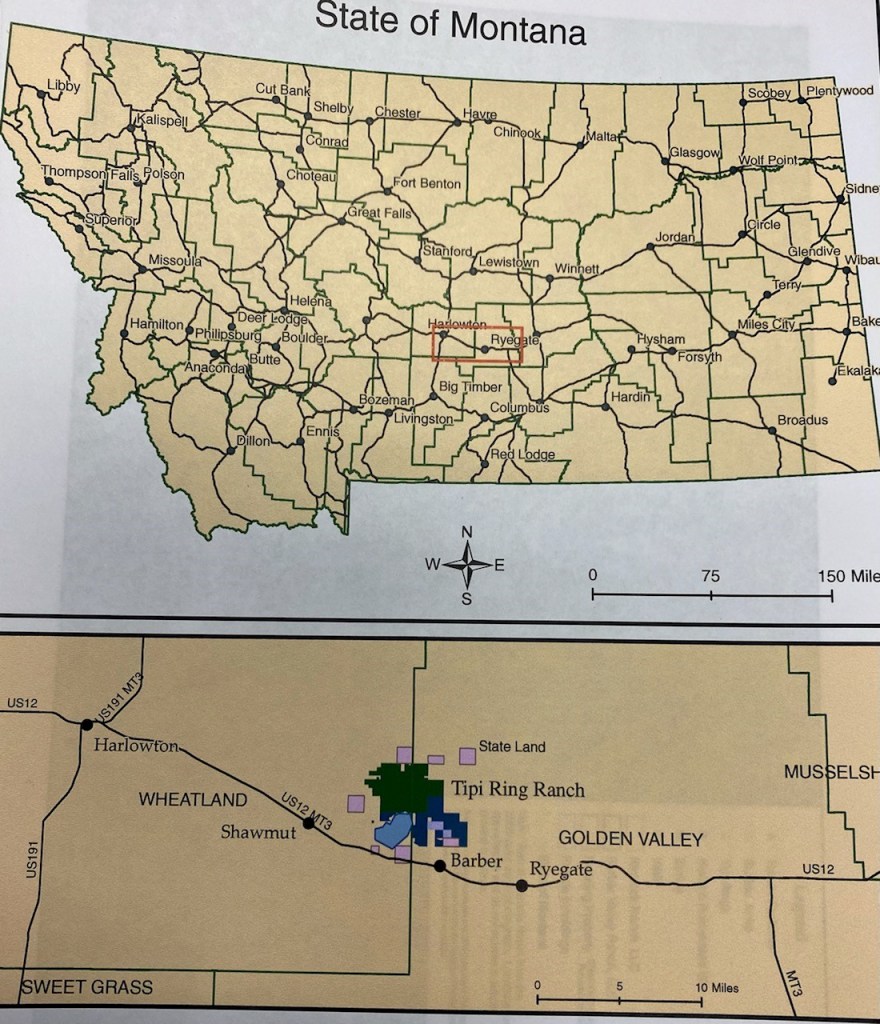

The Tipi Ring Ranch, consisting of the conjoined Rimrock and Barber Valley ranches, comprise approximately 11,000 acres straddling Wheatland and Golden Valley counties in the vast hay, grass, and wheat lands of north central Montana. The footprint of the Tipi Ring Ranch includes Indian camping, hunting, and battle grounds; a buffalo jump; the remnants of early homesteader settlements; a one-room school house; the outer traces of several ghost towns; and the settings for two big-budget Hollywood movies. Over the course of time, the ranch was traversed by Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, Lewis and Clark, Kit Carson and Jim Bridger; any number of hunting and marauding Crow, Blackfeet, and Cheyenne Indians, and more recently by the likes of Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman. The winds that sweep across the land serve to make it a natural grasslands, and have reduced the footprints and traces of human history to a minimum. But the cultural and ecological record is clear, and the memories of second and third generation settlers still residing in and around the ranch are likewise fresh and rich in detail.

In addition to the varied human narrative intrinsic to the ranch, the natural and physical history of the land embraces a complex mix of grass and wetland habitats home to antelope, deer, prairie dogs, and over one-hundred species of birds. Endangered black footed ferrets are suspected to be preying on the prairie dogs; elk have been seen on the ranch; wolves and bears once roamed freely, feeding on buffalo carcasses and fish from the nearby Musselshell River, and terrorizing the early homesteaders and making off with their sheep and cattle. Golden eagles and a plethora of raptors circle beneath the omnivorous sun. The Deadman’s Basin lake that forms a significant portion of the southern boundary of the ranch is home to Kokanee Salmon, huge brown trout, and tiger muskellunge. From the cladgett sandstone rims overlooking the lake there are sweeping views to mountains in every direction: the Big and Little Snowies, Little Belts, Crazies, Castle, and the Absorakees.

Although currently managed for a diverse and sustainable yield of hay, wheat, cattle, and sporting habitat, the Tipi Ring Ranch is the ancestral home for one of the most iconic creatures of the American West: the buffalo. The herds that poured down from Judith Gap between the Snowy and Little Belt Mountains, were legendary in their sheer size and duration. Historians have identified the ranch property as one of the last places where buffalo roamed well into the twentieth century. The Indians came here to hunt the buffalo; Charles Russell came here to paint them hunting along with the cowboys and settlers who sealed the doom of both the buffalo and their native predators. Although the buffalo are gone, the shadow of their presence remains in the historic artifacts still found on the ranch. A variety of Indian beliefs and prophecies contend that the day will arrive when the white men will return to their home lands across the sea and the buffalo will rise up out of the ground to re-form the great herds that sustained countless generations of natives. If that day ever comes, it will surely come first to Tipi Ring Ranch, a land defined by buffalo, by their hunters, and by the early settlers who had the pluck and tenacity to “prove up” at the dawn of the modern Montana era.

WHEN THE BUFFALO ROAMED

Seen from any vista or approach, the Tipi Ring Ranch occupies a beautiful natural setting on gently rolling terrain on the bluffs above the Musselshell River to the south, and below the mountains and passes to the north and west. The unique topography of the ranch made it a vibrant buffalo migration pathway for untold eons in the past. The buffalo were drawn down from the surrounding mountains and passes to a land deep in forage with plenty of water.

With the buffalo herds came the aboriginal Indian hunters, first on foot with spears and bows and arrows, and later – in the 17th and 18th centuries after contact with the French to the north and Spaniards to the south – with horses and firearms. The cliffs to the west provided a natural barrier to predators, although in time, these same cliffs were used by Indian hunters both as ideal campsites, and as buffalo jumps. Donning wolf pelts and waving pine branches, the Indians would form two long lines of warriors at either side of the herd. Other warriors would ride up behind the herd, or even set range fires, to drive the buffalo down the narrowing gauntlet of disguised warriors. At the end of the gauntlet were the cliffs above Deadman’s Basin. Here, the unsuspecting buffalo fell to their death by the thousands, providing the tribes an entire winter’s bounty of meat.

Indian rings attest to the occupation by various tribes. Six such rings – a circle of stones embedded in the grass – can be found on Battlefield Ridge, the sandstone rims on the ranch right above the basin. These rings were used to lash down tipis of the tribal hunting parties. The lofty location allowed observation of the surrounding buffalo ranges, and were used by hunting parties from the Crow, Blackfeet, and Cheyenne. The diversity and abundance of arrowheads and other artifacts found on and around the ranch makes it clear that this was an important hunting ground for the tribes. Studies have shown how the unique patterns of arrowhead construction relate to a tribe. For example, an “atlatl”, or Indian throwing spear, has been found at the site, along with countless arrowheads, tools, and chippings used by a variety of Plains Indians. These artifacts help identify the tribes frequenting the area. An extensive local collection of arrowheads was assembled by historian Harlan H. Lucas of Harlowton. His collection, on display at the Harlowton Museum, has been evaluated and catalogued by Dr. Larry Lahren of the Montana State Uuniversity. In addition to arrowheads and spears, a .44 caliber rimfire Henry’s rifle cartridge lever from an 1866 Winchester was found on the ranch, attesting to the fierce battles fought between the Crow and Blackfeet for control of the buffalo hunting grounds.

In May of 1805, and a year later in July, 1806, the Lewis and Clark expedition passed through the Musselshell country, going and returning from the Pacific coast. It was on the return trip that Captain Lewis passed through and named Judith Gap after one Miss Judith Hancock of Faircastle, Virginia. Upon his return to Washington, DC, Lewis married Judith. His route that summer in 1806 took him near or right across the Tipi Ring lands. Twenty five years later, in the summer of 1830, an exploration party led by Jim Bridger and Kit Carson traversed the same country and surveyed its agricultural potential, again passing directly through the Tipi Ring Ranch country, where they found abundant game, including antelope and buffalo.

The extent of the Musselshell area as a buffalo range can be gleaned from the accounts of early explorers and surveyors who worked in the area. Lt. John Mullen, a young army officer with a railroad survey in 1853, wrote of his travels: “Innumerable herds of buffalo were feeding near the mountains, and the small ponds swarmed with geese and ducks.” (1) In a later mining report from 1870 the author reported “immense herds of buffalo, much sought after by the different Indian tribes.” (2) Captain William Ludlow wrote in his “Report of Reconnaissance from Carroll, Montana Territory”, of “scattered herds of buffalo… on the prairie south of Snowy Mountains.” (3) Martin T. Grande was a pioneer to the Musselshell region. He arrived in the Harlowton area about 1877 and worked as a big game hunter. Grande was reported to have seen on herd “so large it took three or four days for the animals to file through the Judith Gap pass and down to the lowlands (site of the ranch) (4).

Indications further testify to the area as a hunting and fighting ground, particularly between the Crow and Blackfeet tribes. A rock line “fence” demarcation crosses east-west near the western edge of the property between the base of the Snowy Mountains all the way to the Crazy Mountains. Archaeologists believe the fence served as a border between the Crow and Blackfeet territories. The Gros Ventre, Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, Assiniboine, Nez Perce, Flatheads, and Shoshones are known to have frequented the valley because of its fine natural passes or an occasional hunting foray.

The Musselshell country including the Tipi Ring ranch lands were treated with a “hands off” policy by trappers and white explorers. The river was not a navigable stream due to a sporadic flow, often running dry during the middle of the summer. Thus, trappers worked streams closer to the Yellowstone and Missouri rivers. The sovereign rights and homeland territories of the tribes were codified by the Treaty of Fort Laramie, which was signed by all parties on September 17, 1851. The Crow, Blackfeet, and Assiniboine tribes had the Musselshell within their general boundaries. The ranch land was originally in the designated Crow reservation, which was later reduced to their current reservation lands farther east surrounding the town of Crow Agency.

However, by 1853 the US Government was beginning to note the development of the West. Consequently, a series of four railroad surveys to find a most practical route to the Pacific was started. General Isaac Stevens was in charge of the northern survey, passing through the area which would make up Montana. He sent Lieutenant John Mullan into the Musselshell region to find and negotiate peace with the Indians. Within four years a treaty had been struck and a route identified that would essentially be the one followed by the Milwaukee Railroad fifty years later, bringing immigrants and homesteaders to Harlowton, Hedgesville, Wallum, and Shawmut, the four towns – two of which remain, and two of which have receded back into the prairie – that form a circle around the Tipi Ring lands.

It was on this land in 1880 that the last recorded Indian battle took place. A homesteader by the name of Bushard, warned everyone that ten Crow Indians had passed by his place and gone up into the Blackfeet country to steal horses. They brought the horses back to a place several miles east of the DeBufff ranch, which would put it right about where Antelope Road makes a sharp S turn down onto the Tipi Ring lands. The Crow band undoubtedly made camp on the rims at the site of the existing rings. Here, in presumed safety, they recounted the story of their warfaring, horse stealing greatness, and planned their grand entry back onto the Crow homeland and days ride further east. But a Blackfeet party of nearly three-hundred warriors had pursued them over the Snowies and down into the basin, passing right in front of the Bushard homestead. On a warm August morning they ambushed the Crow, killing all but one of the band who they allowed to go free as a warning to future horse thieves. A couple of days later the Crow chief came with medicine men and family members to collect the remains and bury their dead. As was the custom for that time, the burial took place by stuffing the bodies into cracks and crevices in the stone bluffs on the southeast edge of the ranch. Although the skeletons have long-since decomposed or been removed, the colored beads left with the dead can still be found in the mounds formed by ant colonies at the base of the cliffs, carried up from beneath a century of covering dust and dirt.

RAILROAD AND HOMESTEADERS

The Indian era began to seriously implode starting in the early 1860’s, following passage of the Homestead Act in 1862, and the construction of a transcontinental railroad in 1869. The Milwaukee Road rail line across central Montana, arrived in Harlowton and the Tipi Ring vicinity in 1900. Due to fears in Congress that the Homestead Act would lead to poor southerners moving west into the Oregon Territory and creating slave states, the Homestead Act was not passed until after the Civil War. 160 acres was the duly allotted homestead. By eastern standards, this amount of land seemed an economic extravagance, but on the windswept prairies of Montana, which achieved statehood in 1864, it was a barely sustainable working plot. Nevertheless, Civil War veterans, immigrants intent on claiming free land in exchange for becoming a citizen, and impoverished land-hungry city dwellers were all vulnerable to the widely advertised Wheatland County mottos of the day, promoted by the railroad in eastern newspapers:

“Good land is yet cheap and terms easy”

Come to the country that graduated eastern renters to Montana Owners!”

Homesteaders could earn a deeded patent for their quarter section if they “proved up” by living on the land for five years, creating a 10 X 12 square foot structure (which some unscrupulous souls maintained was measured in inches, not feet) and paying a minor title fee. Early settlers in the Tipi Ring Ranch area found the going tough. Norwegians and Swedes were the predominant settler nationalities. The land they settled was rich for wheat, when the rain fell and the hail stayed away. But it was a hostile country, much different from the forests and meadows of Scandinavia. There were few if any trees for a suitable structure, therefore wood had to be hauled from the river bottoms or the distant mountains, otherwise a sod cabin was the only resort. Fuel for heating and cooking was equally minimal, necessitating the use of cow chips or hacking coal from the rimrock seams. It was an extremely hard life, and many, if not most homesteaders, packed up and moved on before “proving up” and claiming their land patent.

One of the earliest homesteaders to settle on the Tipi Ring Ranch was the family of Harley and Anna Sherburn. They settled in 1908, walking four miles from the train station to a friend’s ranch, then another few miles by horse and buggy to their homestead. They built a cabin with one large room partitioned by curtains. Two sisters and a growing passle of children arrived, and soon after the first school was built on the ranch. The Rimrock Basin School eventually had 32 children in the one room “teachery”. The first teacher was a 17-year-old girl from North Dakota by the name of Lola Lila Low, who was known to cry herself to sleep every night from homesickness. She boarded with one ranch family after another. Anna Sherburne was the grande dame of the neighborhood, and was often called upon at any hour of the day or night to help nearby settlers with childbirths, sicknesses, and every manner of homestead problem. Nearby families included the Zeiers, Baldwins, Days, Williamsons, Toombs, Slyders, Mallons, and the DeBuff’s. (5)

But for every ten families that left, one remained, sometimes purchasing the patent or unused homestead for a crate of eggs. In time, the Rim Rock School was dragged down Antelope Road closer to the growing DeBuff family and the school became the DeBuff School. The DeBuff’s from Belgium, along with the nearby Lammers clan from Germany, were two such enduring families that grew their ranches as the homesteaders moved on. The DeBuff family originally homesteaded between Shawmut and Hedgesville, They brought two cows, a steer, and several dogs, living for the first couple of years in an uninsulated shack. Coyotes, bears, and wolves were a constant threat to their growing number of pigs, turkeys, and sheep. It was a half-mile walk in every kind of weather to milk the cows each morning. A twister spun a building completely around on its foundation, and one dust storm was so severe that drifts six feet deep buried many of the fences. They acquired the Rim Rock School for their six children along with ten other neighboring ranch children, literally dragging it down the roads and trails to position centrally to new groups of school age children as one set advanced through the eighth grade, and another set of youngsters were ready to begin. The DeBuff family – Conn and Dan – were the eventual owners of the Tipi Ring Ranch. Conn lived on and gave the ranch its name, and Dan now manages operations on the ranch for its current owners.

Dan’s wife went to high school in the long gone town of Wallum, just around the north east corner of the ranch on the banks of Careless Creek. Dan can show you the shadows of main street, the gridwork of neighborhoods, the pile of bricks that was once a two-story high school. He was there for the filming of “Far and Away”, starring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman (“a brat!). In an unusual bit of film trivia, it should be noted that the original landowner in the train stop at what would later become Shawmut, was a gold prospector and entrepreneur named Thomas Cruze. He discovered the Last Chance Gulch goldmine and later became the richest man in Helena. And Dan remembers when a pivotal scene from “The Horse Whisperer” was filmed at the corner of Ruznick and Wallum Roads on the eastern edge of the ranch, with Kristin Scott Thomas and Scarlett Johansson trying to decide which way to go, east or west. And of course choosing west and their destined meeting with Robert Redford.

A friend and neighbor of the DeBuffs were the Quinns – John and Anne – a brother and sister from South Dakota whose extended family remained in South Dakota and established the famous Wall Drug tourist outpost. John and Anne arrived on what is now the Tipi Ring Ranch lands in 1914 and homesteaded their quarter sections kitty-corner from one another. John was drafted into the Army at the start of World War One. On the afternoon he left to join the 349th Infantry at Camp Dodge, Iowa, he stood in the doorway of his little cabin and threw the front door keys as far as he could out into the prairie, telling his sister Anne, “I may never come back, but if I do, I’ll find a way to get in!” Unfortunately, his words turned out to be prophetic; he was killed in the Argonne Forest in 1918 and was buried in France. Anne remained on the homestead, married a Mr. John O’Connell of Boston, and the two homestead parcels remained in the O’Connell family until they were purchased by the current Tipi Ring owners in 2007 to make the ranch contiguous and whole.

Art Lammers is 96-years-old, with a crystal clear memory of events that happened forty and fifty years ago and longer. He still owns 45,000 acres in the county and is its largest taxpayer. He is one generation removed from the original homesteaders and is a font of stories and anecdotes about living a long life in and around the Tipi Ring Ranch. He remembers tales from the earliest settlers about Blackfeet Indians leaving the Custer massacre at Little Bighorn, and riding right across the ranch to their northern homelands. He heard accounts of Chief Joseph and his ill fated escape with the Nez Perce to Canada, pursued by the relentless General Howard. Chief Joseph also passed across the Tipi Ring Ranch lands enroute to the Bear Paw Mountains due north between the Big and Little Snowies. He remembers his mother came out of her house to call after Charlie Jewel, riding fast on a stolen horse, that he would never get away after robbing the Harlowton Bank of $11,000 cash. Charles Peterson was the bank teller, who recognized Charlie immediately despite a cloth bandana over his face. But Charlie’s brother Cal was waiting with a fresh horse, and Charlie rode off into the sunset, never to be seen again.

The Lammers were one of the first to see the implications of the end of the open range. They put up the first fence between the Musselshell and the Snowies, running first sheep then cattle. During the Great Depression over one-third of the land in Wheatland County was foreclosed on for taxes. Land could be purchased for a dollar an acre. He recalls paying up on the deed of one homesteader who had been driving home from the town the previous day, with his eight children laid out like cordwood on the buckboard horse drawn wagon. It was hailing so the rancher placed a tarp over the children to keep them from getting wet and bruised. But the hail turned to lightning, and when he arrived home he discovered one daughter had been struck and killed. He sold the land the next day to the Lammer’s family and moved on.

AN OLD LAND WITH NEW POSSIBILITIES

The Tipi Ring Ranch is rich in history, but it holds the promise of a new beginning. Renewable wind power is within sight at the massive Judith Gap wind farm. The same winds that power Judith Gap ten miles to the north blow every day at the ranch. And while the homesteaders had to “prove up” to remain on the land, the current owners have “proved up” the solar powered wells and water pumps, the new fences, fields, and roads, and the sustainable harvest plans for CRP management and dry farm crops. The wetlands areas have been fenced off and protected; the inholdings acquired and the ranch made whole.

From the majestic rims, one can still look out across an unspoiled land bordered by a ring of snow covered mountains. Except for the symphony of birds, it is one of the quietest places in Montana, perhaps in all of north America. If you listen hard, you can hear the echo of immigrant trains, bringing eager homesteaders from faraway lands. You can hear the war cry of Indians returning from the Custer battle or a successful horse raid. And if you listen really hard, you can hear the hoofbeat of countless buffalo, stampeding across the ranch, pursued by thunder storms and their own inescapable fate.

TIPI RING RANCH HISTORY

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND FOOTNOTES

- U.S. Congress, Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economic Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific. 1860, House Doc. 56, p. 123.

- U.S. Congress, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains. 1870, House Doc. 207, p. 293.

- U.S. War Department, Report of a Reconnaissance from Carroll, Montana Territory, on the Upper Missouri to the Yellowstone National Park in the Summer of 1875. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1876, p. 15.

- Doctoral thesis, The Upper Musselshell Valley of Montana. Harold Stearns, 1966.

- Conversation with Dan DeBuff, 2009.

- Conversation with John O’Connell, 2009.

- Conversation with Art Lammers, 2009.

- Harlowton Public Library Board, “Upper Musselshell Valley Personalities.” Miller and Schreiber, 1990.

- Harlowton Women’s Club, Wheatland County, “Yesteryears and Pioneers.” 1972.